Pathologic Diagnosis of Malignant Mesothelioma

Separating benign versus malignant mesothelial proliferations presupposes first that the process has been recognized as mesothelial. The diagnostic approach used when distinguishing reactive mesothelial hyperplasia from epithelioid mesothelioma is different from that used when distinguishing fibrous pleuritis from desmoplastic mesothelioma. The major problem areas are discussed in the following.Reactive Mesothelial Hyperplasia Versus Epithelioid MM

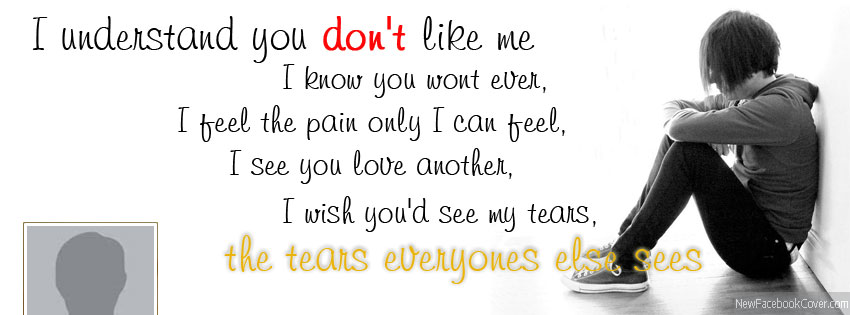

|

| Reactive mesothelial hyperplasia within fibrous tissue mimicking invasion (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification x100). |

Demonstration of stromal or fat invasion is the key feature in the diagnosis of MM. Invasion may be into visceral or parietal pleura (or beyond) and this can be highlighted with immunostains such as pancytokeratin or calretinin. Invasion by mesothelioma is often subtle and may be into only a few layers of collagenous tissue below the mesothelial space. Invasive mesothelial cells may also be deceptively bland in appearance and completely lack a desmoplastic reaction. However, it is emphasized that if a solid piece of malignant tumor, with histologic features of MM, is identified, the presence of invasion is not required for the diagnosis.

Reactive mesothelial proliferations tend to show a uniformity of growth and this may be highlighted with pancytokeratin staining, which show regular sheets and sweeping fascicles of cells that respect mesothelial boundaries in contrast to the disorganized growth and haphazardly intersecting proliferations seen in mesothelioma. Although certain immunohistochemical stains are more typically positive in benign roliferations and others in malignant proliferations, they should not be solely relied on for diagnosis in individual cases. The best known of these include epithelial membrane antigen, p53, and desmin.

The results of Attanoos et al,2 who studied 60 mesotheliomas and 40 cases of reactive mesothelial hyperplasia, are included in Table 2. This topic was reviewed by King et al3 who concluded that desmin and epithelial membrane antigen (membranous staining) were the most useful but that the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for both was less than 90%. They noted that novel markers of proliferation such as MCM2 and AgNOR may be useful adjuncts in this situation but they present technical difficulties and are not widely used. Although elomerase transcriptase expression was suggested to discriminate between hyperplastic and neoplastic mesothelium, subsequent studies showed limited usefulness.

In a recent study by Kato et al,5 GLUT-1 reactivity was found in 40 of 40 mesotheliomas; whereas all 40 cases of reactive mesothelium were negative. A study done at the University of Chicago6 showed all 40 benign mesothelial tissues (20 normal, 20 reactive cases) to be negative for GLUT-1, whereas of 45 MM, 9 (20%) were negative, 34 (53%) were weakly positive, and 12 (27%) were strongly positive. Thus, when GLUT-1 is positive, it is a helpful marker for MM, both epithelioid and sarcomatoid, but is not helpful when negative.

Fibrous Pleurisy Versus Desmoplastic Variant of Sarcomatoid Mesothelioma The identification of features of malignancy in a desmoplastic mesothelioma requires adequate tissue and the amount of tissue in a closed pleural biopsy is often insufficient. Large surgical biopsies are generally needed. High-grade sarcomas presenting in the pleura generally do not enter into the differential diagnosis of fibrous pleurisy versus desmoplastic mesothelioma.

In the study by Mangano et al,7 the distinction of fibrous pleurisy from desmoplastic mesothelioma could be made by identifying one or more of the following features in a spindle cell proliferation of the pleura: invasive growth, bland necrosis, frankly sarcomatoid areas, and etastatic disease. Stromal invasion is often more difficult to recognize in spindle cell proliferations of the pleura than in epithelioid proliferations. The invasive malignant cells are often deceptively bland, resembling fibroblasts, and pancytokeratin staining is invaluable in highlighting the presence of cytokeratin-positive malignant cells in regions where they should not normally be present: in the connective tissue, adipose tissue, or skeletal muscle deep to the parietal pleura or invading the visceral pleura and lung tissue (or other extrapleural structures present in the sample)

Although Mangano et al7 also found bland necrosis of paucicellular fibrous tissue to be a reliable criterion of malignancy, it may be subtle and one may be reluctant to base a diagnosis of malignancy solely on its presence. Fortunately, most cases that show bland necrosis also show invasive growth. Similarly, the presence of ‘‘frankly sarcomatoid foci’’ is a distinctly subjective determination and one would be reluctant to base a diagnosis of malignancy on its presence alone because reactive processes may show marked cytologic atypia, albeit typically at the surface of the process.

Uniformity of growth and thickness of the process, surface atypia with deep maturation, and perpendicular thinwalled vessels are typical of reactive fibrous pleuritis, in contrast to the disorganized growth pattern and variable thickness of desmoplastic mesotheliomas. A helpful clue in desmoplastic mesotheliomas is the presence of expansile nodules of varying sizes with abrupt changes in cellularity between nodules and their surrounding tissue.